Standing Bear. Blu Barnd. Orange.

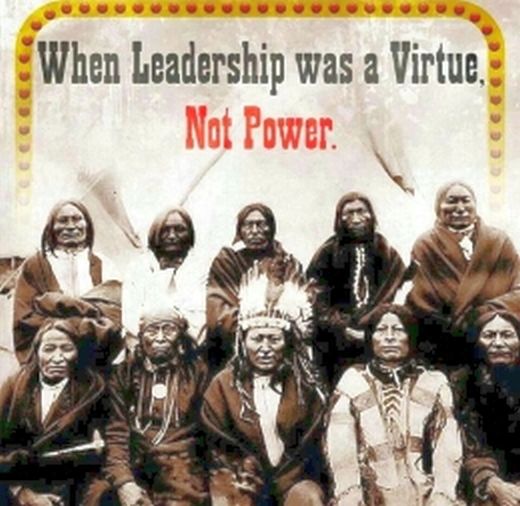

Wherever forests have not been mowed down, wherever the animal is recessed in their quiet protection, wherever the earth is not bereft of four-footed life – that to the white man is an ‘unbroken wilderness.’

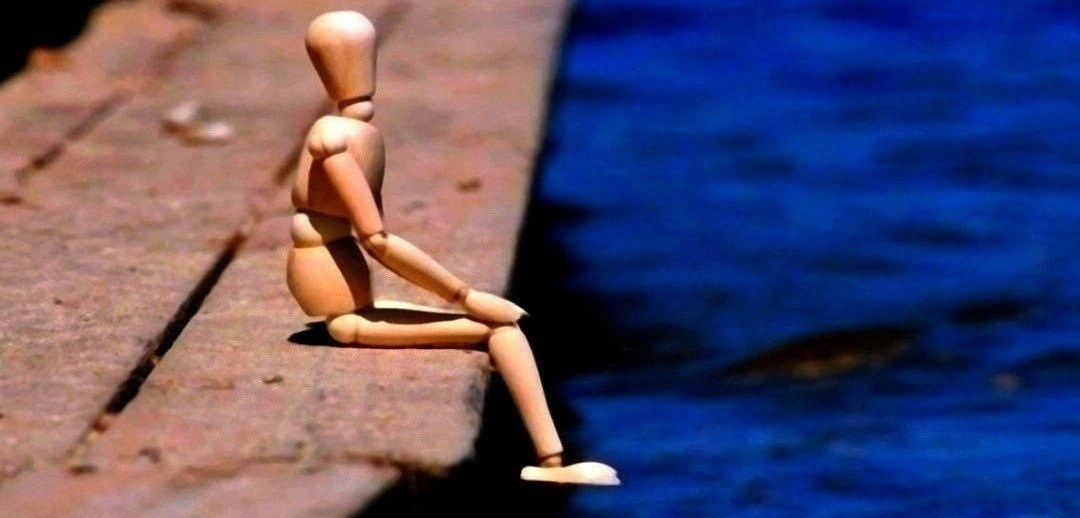

But for us there was no wilderness, nature was not dangerous but hospitable, not forbidding but friendly. Our faith sought the harmony of man with his surroundings; the other sought the dominance of surroundings.

For us, the world was full of beauty; for the other, it was a place to be endured until he went to another world.

But we were wise. We knew that man’s heart, away from nature, becomes hard. Chief Luther Standing Bear.

During the initial colonization of the Americas, the imposition of new names on the landscape reflected European need and desire for justifiable occupation of Native lands. Renaming and claiming territories delegitimized Native land rights and Native knowledge. As new European-derived names were deemed more appropriate for freshly “civilized” spaces.

Many namings were explicit acts of appropriation and statements of individual land claims. Others were chosen to extend European cultures and geographies symbolically (for example, New England, Cambridge, and Virginia). Even where such explicit Europeanizing of the named landscape was not present, however, colonial designations often belied their colonial implications and intent.

New York City’s Wall Street, for example, originated as a tool for protecting colonial space and actively excluding Native peoples while claiming the land from under their feet. Although the Dutch eventually abandoned their colonial post on the island when driven out by the English in 1664, their fortified walled street remade a Native landscape into a space that discursively and physically protected invading settlers from Native inhabitants and thus marked Native peoples as dangerous trespassers on European lands. Natchee Blu Barnd.

We didn’t have last names before they came. When they decided they needed to keep track of us, last names were given to us, just like the name “INDIAN” itself was given to us. These were attempted translations and botched Indian names, random surnames, and names passed down from white American generals, admirals, and colonels, and sometimes troop names, which were sometimes just colors.

I asked my mom what we were gonna do. She told me we could only do what we could do, and that the monster that was the machine that was the government had no intention of slowing down for long enough to truly look back to see what happened. To make it right. And so what we could do had everything to do with being able to understand where we came from, what happened to our people, and how to honor them by living right, by telling our stories. Tommy Orange.